Utility

- Monotonic transformation refers to the transformation of a (utility) function, u, by a strictly increasing (AKA monotonic) function, f

- Mathematically, this is written as f(u(x))

- This transformation does not change the indifference curves or preference ordering; the only thing that is changed is the magnitude of the outputs

- This means that the MRS of a preference relation will not change

Showing how the MRS does not change using partial derivativesu(x1,x2), MRSu=−∂u/∂x2∂u/∂x1Let v be a monotonic function and represent a monotonic transformation: v=f(u)MRSv=−f′(u)⋅∂u/∂x2f′(u)⋅∂u/∂x1=−∂u/∂x2∂u/∂x1

This proof also shows that any function transformation will not affect the MRS. However, non-monotonic transformations will destroy the order of the preference relation.

Choice

- Rational Constrained Choice refers to how consumers choose a bundle based on their constraints, such as budget

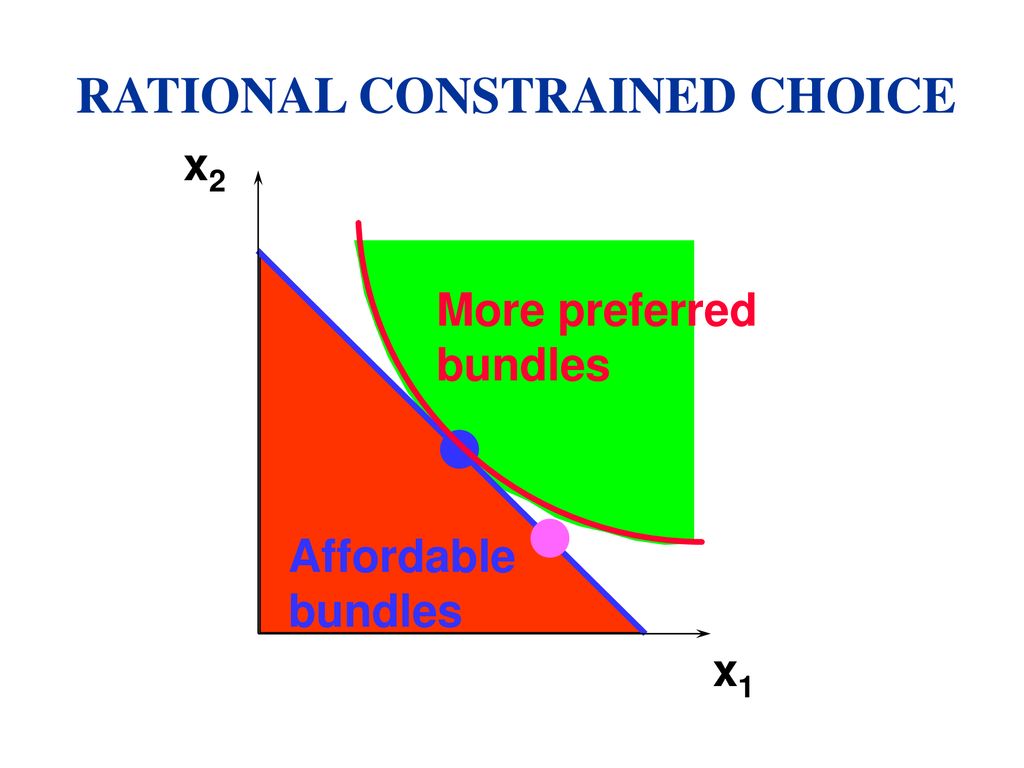

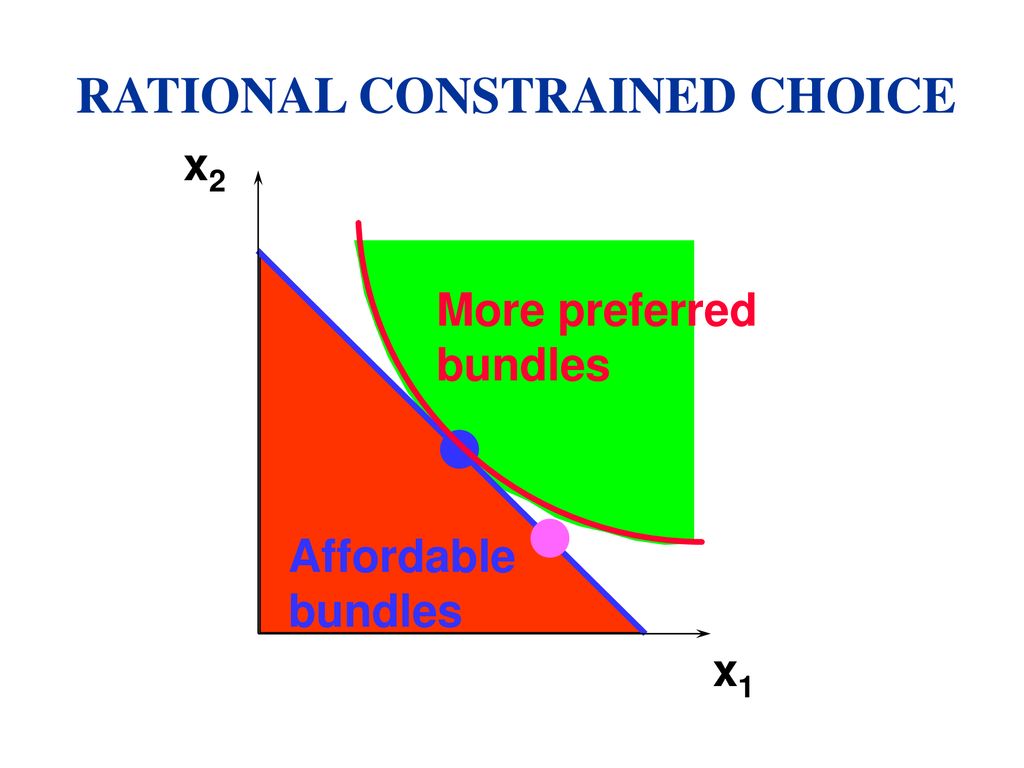

- Consider the following graph:

- The point on the indifference curve that both intersects the budget constraint (represented by the straight line) and is tangent to it is the most preferred affordable bundle, as there are no strictly preferred bundles to it

- Other affordable bundles have strictly preferred bundles to them, and the strictly preferred bundles are not affordable

The most preferred affordable bundle at given prices and income will be denoted x1∗(p1,p2,m) and x2∗(p1,p2,m)These are functions that will change based on the prices and income.When x1∗>0 and x2∗>0, the demanded bundle is known as an interior solution.When x1∗=0 or x2∗=0, the demanded bundle is known as a corner solution.If buying (x1∗,x2∗) costs m, then the budget is exhausted.

Requirements for the most preferred affordable bundle:

Assuming that (x1∗,x2∗) is interior, we make the following assumptions:(x1∗,x2∗) exhausts the budget. That is, p1x1∗+p2x2∗=mThe MRS of the IC at (x1∗,x2∗) is equal to the slop of the budge constraint.The second condition is violated when considering corner bundles.

Solving for the most preferred affordable bundle at the interior:

u(x1,x2)=x1ax2bMRS=−bx1ax2b−1ax1a−1x2b=−bx1ax2At (x1∗,x2∗),MRS=−p2p1Equation A: −bx1∗ax2∗=−p2p1→ap2x2∗=bp1x1∗Equation B: p1x1∗+p2x2∗=mPlugging A into B: x2∗=ap2bp1x1∗p1x1∗+p2ap2bp1x1∗=mp1x1∗(1+ab)=p1x1∗(aa+b)=mx1=(a+b)p1amPlugging x1 back into Equation A: ap2x2∗=bp1(a+b)p1amp2x2∗=(a+b)bm→x2∗=(a+b)p2bm(x1∗,x2∗)=((a+b)p1am,(a+b)p2bm)This final solution shows that the a and b in the Cobb-Douglas equation represent the proportions at which good 1 and good 2 are bought/preferred

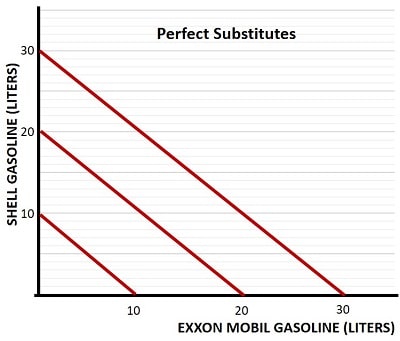

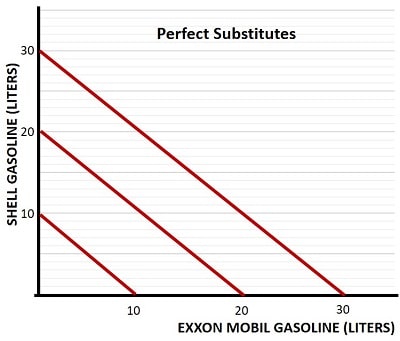

One use case for corner bundles is when goods are perfect substitutes, as a consumer would spend their entire budget on the cheaper good and buy none of the more expensive one. Recall that the graph of the ICs for perfect substitutes looks like this (slopes of -1):

If the price of one good is cheaper than another, then the BC would intersect both the highest IC (when purchasing all of cheaper good) and lowest IC (when purchasing all of expensive good). This is because the slope of the BC (-p1/p2) is not -1 if the prices differ. When the prices are the same, any bundle on the budget constraint will do, as all the bundles on the BC belong to the same IC.

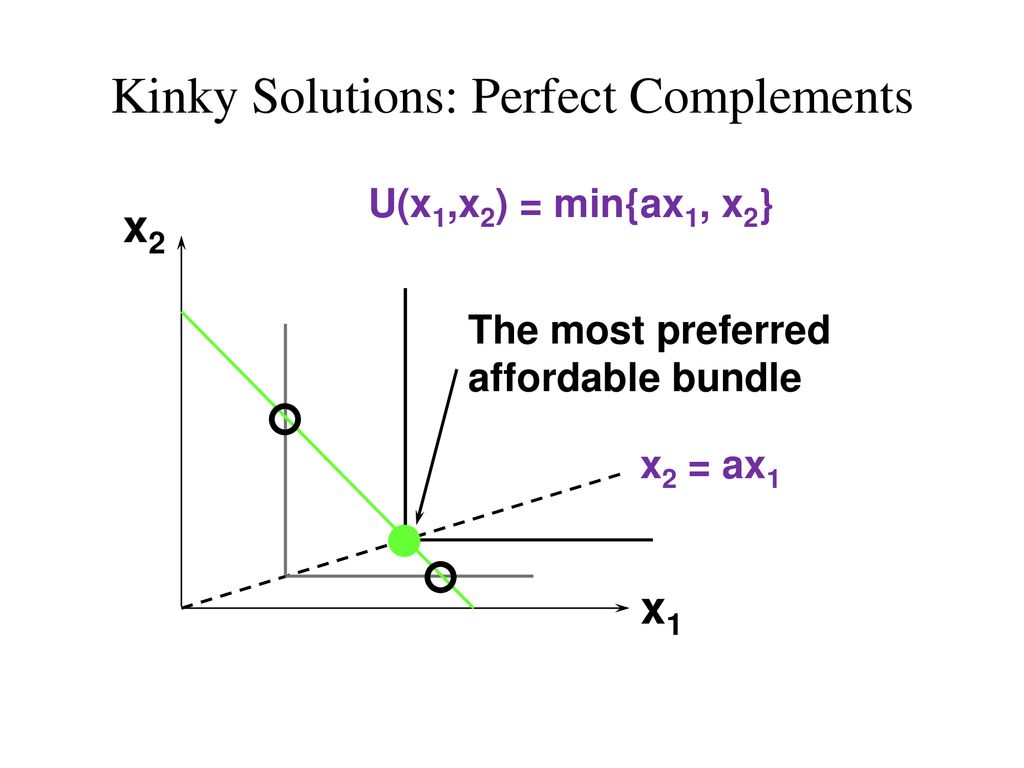

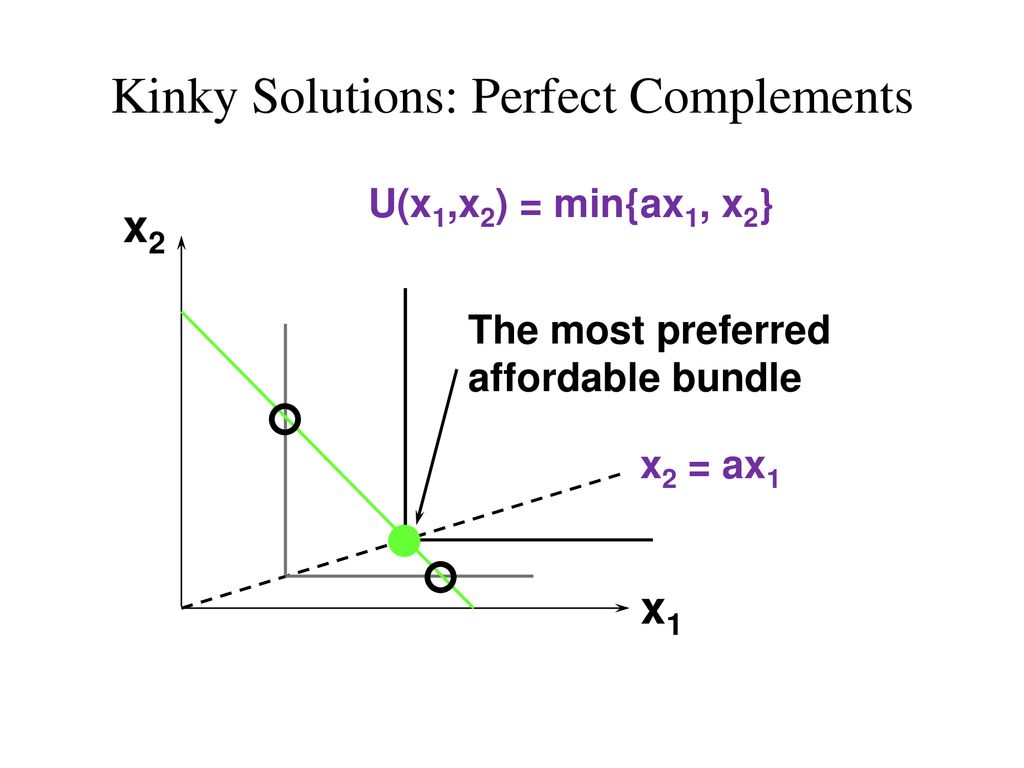

Perfect Complements

Recall that if two goods are perfect complements, then the utility function takes the form u(x1,x2)=min(ax1,x2)

In this case, there are no corner solutions, and you can draw a line through the kinks. The intersection of the line through the kinks with the budget constraint thus gives the most preferred affordable bundle.

ax1=x2 represents the line of "perfect consumption"; that is, no units of good 1 or 2 are wasted.To find the most preferred affordable bundle, the bundle should lie on ax1=x2 and on the BC.Equation A: ax1=x2Equation B: p1x1+p2x2=mPlug Equation A in to B:p1x1+p2(ax1)=mx1(p1+ap2)=mx1=p1+ap2mx2=p1+ap2am